In November 2018, He Jiankui sparked international outrage when he announced his genetic engineering results to the public. Using a powerful gene-editing tool, CRISPR, He Jiankui and his team at the Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen apparently modified human embryos to give them resistance to the HIV virus. Two of these embryos, twin girls Lulu and Nana, were later reported to have been born healthy and now exist as the world’s first genetically-edited human babies. Here is He Jiankui presenting his gene-editing work at the Second International Summit on Human Genome Editing.

Most genetic scientists condemned He Jiankui’s work as a horror straight out of a dystopian novel, with some like Dr. Kiran Musunuru from the University of Pennsylvania calling it “unconscionable” and “not morally or ethically defensible.” Yet there were still some who supported He Jiankui’s efforts. For instance, George Church, a geneticist at Harvard University, deemed gene-editing for HIV “justifiable” due to the disease becoming “a major and growing public health threat.”

While I personally think it to be arguable as to whether He Jiankui’s gene-editing attempts on human embryos were “justifiable,” I do believe them to be the advent of a new age of humanity. Inevitably in the future, our scientific capabilities will reach a point where gene-editing human babies is much safer and easier than it currently stands.

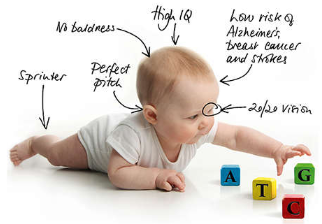

Perhaps in some areas, the controversy behind the practice will diminish to a minimum by then. Already with He Jiankui’s work, we can see that some scientists like George Church agree with the underlying noble endeavor to eradicate deadly diseases from humanity’s concern. The picture below depicts some gene-editing possibilities for humans in the future.

However, looking at other avenues human gene-editing could traverse, I see a major gray area most notably with genetically engineering intelligence. With gene-editing tools even more powerful than CRISPR, could we finally succeed where so many hopeful parents have failed in creating “geniuses?” Even if every country banned human gene-editing like what the United States and many other countries have already done, how can we know there won’t be any corruption in the field of gene-editing? Who’s to say some scientist won’t accept a load of cash to make some rich couple’s baby the smartest human in the world? An even scarier thought is how would anyone even find out if a baby had been genetically-edited?

These are serious questions that will only get asked more frequently as we head into a human gene-editing age, and I could probably discuss their ethics at length. However, I’d rather briefly discuss the biological basis of genetically engineering augmented human intelligence. Science has supposedly discovered so-called “intelligence genes,” which means we can somewhat predict a person’s intelligence from his/her DNA. But how do “intelligence genes” actually manifest themselves in a person, and is genetically engineering human intelligence even possible?

To start, you may have heard of the genome. You know, it’s that fancy word which just means the entire sequence of your DNA. You’ve also probably been convinced at some point in your life that you were unique because of your genome, as no two people, not even identical twins, have the exact same DNA. Well, let me amend that belief — in fact, let me teach you an even fancier word which more accurately explains your uniqueness: connectome (here’s the talk that got me interested in connectomes).

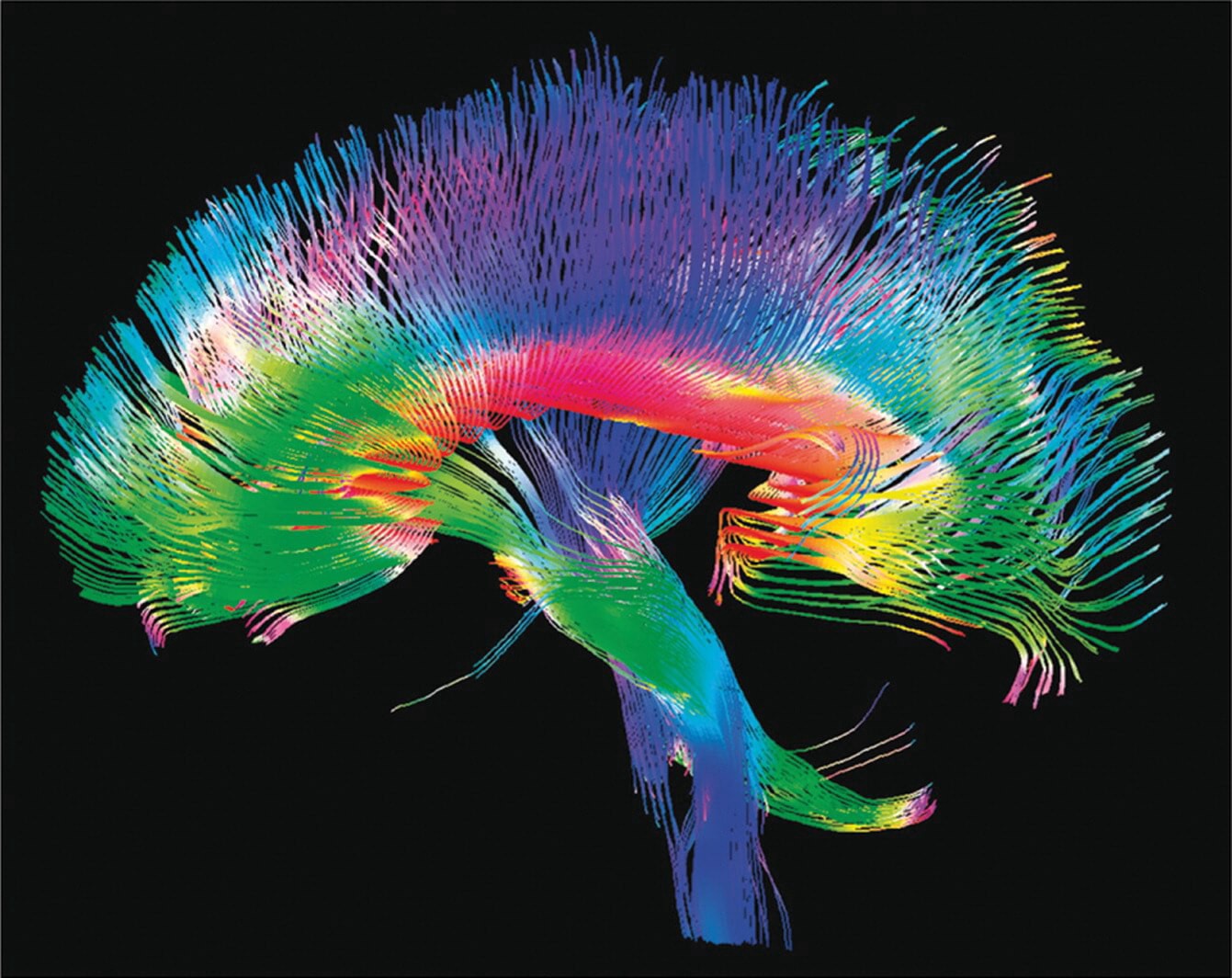

In the human brain, there are billions of neurons connected by trillions of extremely tiny junctions called synapses (there’s actually a lot of other stuff, but that’s for another day). Every human brain has a unique combination of neurons and synapses which we call his/her connectome. Unlike your genes, the connections in your brain are malleable, changing with every little input into your sensory system. For example, as I’m typing this sentence, the neural connections pertaining to the mechanical movement of my fingers hitting the keyboard and the visual recognition of my eyes seeing the letters on my computer screen are all changing. However, my genes remain static — they couldn’t care less about what I’m typing. The picture below depicts a crude yet rather aesthetic rendering of the human connectome.

Because our connectomes basically adjust every moment, we should theoretically be able to find all of your life experiences encoded within them: your memories, your feelings, your personality, your intelligence — everything. As you grow older and are exposed to various social and environmental experiences, your connectome changes in ways unique from any other human being on Earth. Effectively, your connectome, not your genome, is what makes you you.

Now, with this knowledge, I shall try to address the question of how “intelligence genes” actually manifest themselves in a person in the most plain way possible.

Suppose we asked 100 babies to solve a problem, and their solutions were represented by the electric field diagram below (do I get extra points for using what we’re currently learning in AP Physics C?). Some babies, represented by the various paths protruding from the plus symbol, will take a roundabout way to reach the solution, represented by the minus symbol, while others might never do so at all.

Still, there are going to be some babies who travel directly from the plus to the minus symbol, which I believe to be a result of their connectomes. Somehow, the brains of these babies are wired in such a way that they are not only are able to solve the problem, but also recognize the most efficient manner possible.

“Intelligence genes” are what cause these differences between people’s innate brains. Some people have more of these “intelligence genes,” which basically means that while they were still developing as fetuses, their genes guided the formation of their neural connections in such a manner that would later manifest itself as “intelligence.”

So how does this relate to our other question, which asks whether genetically engineering human intelligence is even possible?

Well, with developing technologies such as expansion microscopy and artificial intelligence set to revolutionize the field of connectomics in the coming years, at some distant point in the future, we should be able to map an entire connectome. This is incredibly astounding because let’s say we knew the connectome of Albert Einstein — what would stop us from combining what we know about genetics and neuroscience and growing the brain of Albert Einstein in a human embryo (besides this oversimplification, of course)? I know it’s crazy to think about given the current state of connectomics, but I implore you to truly consider the power that this field holds. If we know all of the various neurons and synapses that compose someone’s connectome, we might be able to encode a set of genes which recreates that exact brain (in light of this discussion, I’m slightly disappointed I don’t have enough time to talk about mind uploading).

As a final note, I’d like to clarify that by no means is “intelligence” entirely inherited. A person’s natural “talent” will never be sufficient without the proper life experiences to change his/her connectome, nor will someone with less “talent” be unsuccessful at what he/she does. But given the recent news regarding He Jiankui’s human gene-editing attempts and the impending innovation of connectomics technologies, all I can say is science will perhaps eventually bring upon a future where it may be possible to manufacture “talent,” which is both extremely scary and cool to imagine.